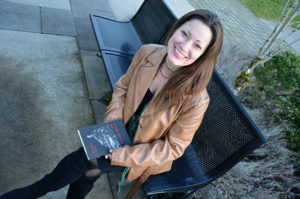

An interview with Jessamyn Smith.

By SAMANTHA WOOD

WEST COUNTY – People in Franklin County are coming down with the illness caused by the new coronavirus, COVID-19. While testing is still hard to come by, the virus is spreading in the community and making people sick.

According to Franklin Regional Council of Governments public health nurse Lisa White, the most important thing now is care for people who are ill. “We should assume anyone we come in contact with may be carrying the virus,” White said in an interview this week.

Jessamyn Smyth, a Franklin County hilltown resident who is recovering from COVID-19, says she is at high risk for complications, and did everything she could to avoid catching this virus. She thinks it was likely that she was exposed through her partner, who was working outside the home but has remained asymptomatic.

Smyth, who has a background in public health and teaches communications, granted the Montague Reporter an interview by email because COVID-19 makes her cough. In the last week, she has experienced respiratory distress and has been to the emergency room. She continues to recover at home as of press time, and is still awaiting test results.

This interview has been edited for length.

Montague Reporter: What were the first signs you had of coronavirus? How did you get tested?

Jessamyn Smyth: I had a feeling of intense pain and pressure in my chest. The next morning I woke up with a fever of 100 and a spasmodic cough, full body pain, GI issues, worsening lung pain. That seems like a long time ago now (it’s been a long week and a half or so!).

Because of test shortages, while I was still breathing okay I didn’t meet the criteria for one of the few tests in Western Mass., even though I am in a “medically vulnerable” group. When I started having real breathing difficulty, my primary care doctor referred me to the emergency respiratory clinic set up in Northampton.

The doc there was both extraordinarily kind and realist, diagnosing corona, discussing what that may mean for me in particular, safety planning with me about when to bolt for the ER and how we hope I won’t have to, all of that. The nasopharyngeal swab used in the test is pretty uncomfortable, but she was even very honest with me about that – I appreciate how she treated me with calm, exact kindness, and respectful directness about both the disease and my risks, more than I can say. I’m grateful for all the work healthcare people are doing right now. They are exhausted already.

MR: How do you think you were exposed to the virus?

JS: Knowing that my hereditary primary immune deficiency and allergy to all groups of antibiotics makes me high risk for complications of coronavirus (and difficult to treat if I got it), I took this contagion very seriously far before most folks around me really understood the dangers. I began fully self-isolating on March 10, teaching and working virtually.

My partner began isolating at home with me on March 15, but was exposed to several high risk vectors in the interim. The span the docs here are seeing between exposure and symptoms for those who get sick is four days, so it seems I got it from him during that period. He’s asymptomatic, which, we have learned from recent studies published in Nature, as many as 60% of all carriers are. That’s 6 in 10 people transmitting with no visible symptoms.

[Editors’ note: Franklin County public health nurse Lisa White told us this week that the incubation period may be up to two weeks.]

This is why self-quarantining matters, and we have to get this message out. People think they (and their kids and their kids’ activities and their back and forth to this and that house and etc.) are okay – and they aren’t, so they are putting other people’s lives at risk.

Everyone needs to isolate themselves and their families in place until we get a better handle on this virus, and use technology to maintain social and familial connections. Anything else, at this point, will be lethal.

MR: Have you been told what you might be able to expect during the illness?

JS: COVID-19 is fierce and brutal, and unlike any illness I’ve felt. I’m told my symptoms – high fever for a long time, extremely painful lungs, coughing, GI symptoms, bone, joint, and muscle pain, weakness and exhaustion – are the common constellation. The lung pain is bizarre, and quite scary.

I’m told that if all goes well, I can expect to be seriously sick for 2-3 weeks, that the exhaustion after the virus sticks around for a month or more depending on how much damage was done, and that some people need respiratory therapy to regain normal lung function.

If all doesn’t go well, bacterial infections take advantage of the virus-weakened lungs, people get bilateral pneumonia and can’t breathe, and they rush to the hospital for respiratory support (ventilator, other forms of life-support – and antibiotics for the bacterial aspect, which are unfortunately life-threatening for me).

I’m a swimmer and cyclist, and so very strong in spite of the immune system issue. I asked the doc who diagnosed me if being fit would help me, hoping it would: she said coronavirus truly doesn’t care. It either complicates or it doesn’t, if I understand correctly, in largest part because of random factors in each person’s immune response and bacterial situations. It can certainly be complicated by existing issues, but life or death with COVID-19 not a moral issue. It’s not a behavioral choice. This is a vicious disease that is extremely communicable and dangerous.

MR: You have written about disability, and now about disability rights in the pandemic. What do you want people in our community to know/think/do about this issue?

JS: What happens when people go into respiratory emergency is when we face what is fast becoming the ethical and legal battle of our time. The inadequate number of ventilators available to cope with the casualties of COVID-19 is causing medical personnel around the world to be having to choose who gets lifesaving treatment and who is left to die.

For people with disabilities, as a result, the word “triage” has begun to inspire terror, because many are willing to talk about this in the language of eugenics and social Darwinism, quickly and easily discarding the value of the lives of our elders and anyone who is “medically complicated,” i.e.: disabled.

Aktion T4, the Nazi program to eradicate people with disabilities, is very much on many advocates’ minds these days as some of the language we hear in current media mirrors that of older genocidal framework. More prosaically, we are feeling the dangerous escalation of the daily assumptions we too often live with: that our work, our art, our community involvement, our contributions to the economy, our bodies, are worth less than those of (temporarily) able-bodied people’s. Italy in particular has been sharing tragic and horrific stories on this “rationing” front, but it has begun happening and being planned for here, too: people are very openly saying that only young, healthy people should be given the ventilators, while our elders and people with disabilities should be left to die rather than “wasting” resources on them when they might be harder to save.

There are currently multiple complaints and budding lawsuits filed with the US Department of Health and Human Services’s Office of Civil Rights over “treatment rationing plans” which, in direct violation of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), discriminate against people with disabilities – including anyone elderly.

All of us can support these, and be in touch with our legislators about this issue.

While I understand the pressures health care systems and doctors face, it is so important for everyone to understand that the difference between a disabled person and a (temporarily) able bodied one is one fraction of a second or an inch in a car crash, one genetic twist, one illness, or, most inevitably and simply, some years. Every single one of us will become disabled to greater or lesser degrees, if nothing else, simply by aging.

We are not in the business of ascribing worth to some lives and not others. The ventilator problem must be solved by making more ventilators. The personnel issues must be solved by making more personal protective equipment (PPE). And so on.

Everyone can support this, too. Working to improve access to medical supplies across the country will save thousands upon thousands of people’s lives.

People can also speak to their local hospital administrators, and require both transparency and dialogue about how the hospital will be making the transition from ethics driven by individual-centered care (what we do in normal times) to ethics driven by community-centered care (what we have to do in pandemics). They can work with their local hospitals to establish exactly what is needed to care for people in a just way, and how we as a community can make that happen, even imperfectly.

Disability Discrimination Complaint Filed over COVID-19 Treatment Rationing Plan in Washington State

MR: Have local public health officials been checking in with you? Do you know if they have charted your recent contacts?

JS: They would have had to track my asymptomatic partner and the (also probably largely asymptomatic) vector-networks through which he got it. The docs are as certain as they can be that I quarantined before getting the virus, and infected no one as a result.

[When reached this week by the Montague Reporter, the chair of the local board of health in Smyth’s town said there are currently no known cases of COVID-19 in their town. When presented with this story, they clarified, saying that the only data they have to work with is the daily update in the state system, which is based only on positive test results. Clinical diagnoses – when, absent a test result, a medical professional assesses a patient and comes to the conclusion that all the symptoms point to COVID-19 – are not entered into the state system. These cases are not being tracked.]

At this point, though, here is the important part: we are in “community spread.” This public health term means that the disease can no longer be tracked through that one person who went out of the country or was on that one cruise ship or whatever – it is transmitting widely and invisibly throughout the community, and as more and more tests become available, we will see that it is already everywhere.

Tracking individuals is no longer the strategy. And of course, targeting individuals who are sick, or scapegoating them in any way, is not only stupid but dangerous: it’s here, people have it, they are transmitting it without knowing they have it, vulnerable people are dying, more will die, and “flattening the curve” by staying home in self-quarantine, hard as that is, is the best tool we have to try to keep our hospitals up and running.

The social and public health strategy needs to be community-wide response with information toward prevention for those who haven’t yet gotten it, and a wide array of supports for those who were already exposed. These approaches need to go hand in hand, so as few people as possible get sick and those who already are sick can recover.

People who are saying “there are no cases in…” are kidding themselves at this point: what they can accurately say is “we haven’t had any positive tests reported to us yet in [X town], but everyone should assume that the corona virus is here, a lot of the transmission is invisible, and we need to be taking every precaution we can.”

This is why I have been willing to share some of my experience publicly by talking with you, or sharing my experience or good public health information or advocacy opportunities in my Facebook network of writers and professors who have communication and education platforms of their own: we need to lay aside the misconceptions we cannot afford, and get it right. Now. Lives depend on it as we have never seen.

MR: You told me you have a background in public health education. Can you explain a bit about that, and how that has informed your response/perspective to this situation?

JS: I teach interdisciplinary Humanities at Bard Microcollege in Holyoke, and also do advocacy and public relations for Stavros (a disability advocacy organization) in Amherst. When I started my career in the ‘90s, I worked in HIV counseling and testing, harm reduction, domestic violence and sexual assault crisis response and prevention, and community education for violence prevention and justice. I now integrate that public health work into the teaching of writing and communications, fine arts, and community building.

In this pandemic, we have a perfect storm of vulnerabilities becoming visible: people who are quarantined with their batterers, homeless or incarcerated or undocumented people who cannot get help or escape the virus, medically vulnerable people with disabilities being discussed in mass media as essentially ballast, and a media moment of echo chambers in which people are getting very bad information and little else, which is spreading the virus and preventing smart and coordinated public health response nationally.

Any voice I have, and any understanding I can gain and refine and share, I want to use in service of protecting the most vulnerable among us. Part of that is really listening, learning from, and understanding the experiences of the most vulnerable. Part of that is raising awareness in more privileged people about how they can be using their positions to help rather than make it worse. Part of that is being willing to share my own experience, at times, when that can be appropriate or helpful.

Mostly, right now, I have to focus on getting well, and hope I don’t get the complications so many people have already faced. But while I’m doing that, I can give what information and advocacy I can to my communities. And I have been deeply moved by how much kindness and loving support many of my communities have offered me; it’s really been holding me up through this.

We are at the point of there needing to be one public approach to this: assume that you have been exposed already, and act accordingly to protect the medically vulnerable people around you, who are much more likely to get fatal complications if you infect them. Stay home.

This is what we have now, yes? Each other. It sounds a lot cheesier than I usually am, but it really might just be the big truth.